The generic characteristics of the intro songs of anicoms; The Simpsons and Family Guy.

Ever since The Flinstones (1960-66), The Jetsons (1962-87) and The Simpsons (1987-) animations also started to focus on adults, as a result of which the genre the ‘animated sitcom’ or ‘anicom’ was created. The anicoms, however, is not a sub genre of the sitcom, but merely a manifestation of the sitcom. The anicoms distinguishes itself from live-action television through animation and the possibility to alter the script in endless fictional ways. The specialty of animation has been preserved by just adding the generic characteristics of the sitcom, which led to a transcendence of both genres while pushing the boundaries. Through Martin Kutnowski’s article ‘Trope and Irony in The Simpsons’ Overture’ (2008) I’ll compare the generic characteristics of the The Simpsons-ouverture with the intro song of Seth MacFarlanes anicom Family Guy. With this, I hope to paint the audiovisual characteristics that ensure that the genre anicom is recognizable from the intro song. I will be using Ronald Rodmans essay Tuning in: American Narrative Television Music (2010) including two, by him described, models for media analysis.[1]

According to Ronald Rodman, television is a love triangle consisting of the physical television device, the images and the sounds that the story and information on screen producer, while the audience interprets this audiovisual context. The audience receives help to interpret these images and sounds by the role of music as a functional mechanism in the television structure; in this case, by signaling when the show starts. As these moments are often short-lived, like the Family Guy theme song (thirty-two seconds), television’s possibility to convey a message strongly depends on its probability; namely, through filling in the narrative holes by calling on contextual knowledge of the audience and repeating conventional references. Because of this, television is a means of miscommunication consisting codes which the viewer has to decode to extract meaning. Rodman introduces a model, drawn by Christian Metz in 1974 for film, but states that this model is also applicable to television. This model shows five observable channels with which is communicated. The combination of these five channels, the red overlapping area, should form a meaning.[2]

Besides, Rodman talks about three levels of audiovisual meaning based on John Fiskes hierarchical scheme of television codes from his book Television Culture (1987);

Musical reality; to be gained from an analyses that is encoded through technical codes, like

representation from audiovisual context. This conveys audio- and visual conventions that shape the story by the means of stylistic and structural codes, which makes you think about

ideology or interpretation. This interpretation is determined on the basis of ideological, dramatic and social codes.

I’ll use both of these models for television to find the codes of communication of the animated sitcoms with help of the audiovisual characteristics of the theme songs of The Simpsons and Family Guy. And with that, I’ll take a look if these theme songs contain enough codes to make the genre clear to the viewer.[3]

The audiovisual message of the The Simpsons-ouverture, composed by Danny Elfman in 1989 and orchestrated by Alf Clausen, contains the essential underlying theme’s of the show, while they introduce the physical, behavioral and psychological profiles of the five family members in the setting of the provincial American culture of the fifties, sixties and seventies. Here, the music is a powerful generic instrument: different conventions refer to the comical, but also to the specific of the show combined with the fast passing images. The music fits the convention of cartoons being led by music. For example; visual gags or shots’ endings are accentuated by musical cadences, a rhythmical choreography of images is applied to the music, mostly by using the technique of Mickey Mousing, and there is a certain state of mind that goes along with the music:[4]

“For instance, horizontal displacement of the clouds is painted with harp glissandi – the “gliding” motion of the clouds in the sky is visually analogous to the hand horizontally gliding through the strings of the harp.”[5]

Besides, ‘hit points’ are often used. These are visual events highlighted by musical accents, so that the comical and animatic effect, like conventions of slapstick and pantomime, is strengthened. The difference with the term ‘sync point’ of Chion is to be found in the difference between live-action and cartoons, in which cartoons do not produce its own sound. And with that, a ‘sync point’ is a synchronisation of image and sound, in which sonic layers are added later on, while a ‘hit point’ always has to be produced in its entirety. The overture presents itself as a baroque ritornello, whereby the familiy members are presented by the means of thematical variation and motivic development. This musical representation also presents the underlying relationships combined with shifting keys.[6]

Music, visuals and narrative are all logically bound to project absurdity and irony, addressed to the dysfunctional life of the Simpsons. This portrays an updated, naturalistic, sobered version of the American dream which offers us an alternative for the decades of television which established an image of the provincial family life as stable and neat including values about consuming, codes of conduct and gender patterns, while presenting them as endless and universal. This image is painted off as the ultimate human condition by using imaginary gadget-conscious elements, like the sprint to the television at the end of the overture. When we dive into the music; The Simpsons uses the Lydian scale; which holds the convention for the American dream and magic values, in accelerated tempo; which in its turn represent the ironic iconic values of an idyllic district. This fits the idea of an anicoms, in which every episode, despite the physical an psychic events, ends well according to the psychoanalytical theory of writing comedy.[7] This accelerated tempo should represent the hectic element of the anicoms which marks the genre as utopic dystopic. Besides, the anicoms often delivers criticism to the world, but also to itself. Through referencing older anicoms, sociocultural and political subjects and themselves, a mirror is placed of the provincial life, in a satirical, absurd and comedic way.[8]

Through an audiovisual analyses of the theme song of Family Guy (1999-), composed by Walter Murphy, I’ll make a comparison of the elements to be found in The Simpsons.

[Verse: Lois Griffin]

It seems today

That all you see

Is violence in movies

And sex on T.V

[Bridge: Peter Griffin]

But where are those good old-fashioned values....

[Bridge: The Griffins]

On which we used to rely?!

[Chorus: All]

Lucky there's a family guy!

Lucky there's a man who

Positively can do

All the things that make us...

[Fill: Stewie Griffin ]

Laugh and cry!

[Outro: All]

He's our Fam-ily Guyyy!

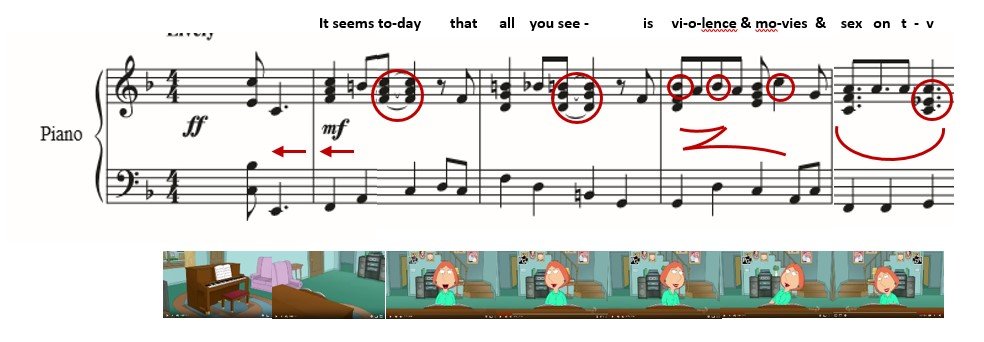

The screen starts from a corner with a sforzato in brass on the dominant of F-major. Usually, on this sforzato, we’ll see the family sitting in the living room, but the screen turns to another perspective; one of overlooking a piano, after which Loïs takes a seat guided by a walking contrabass, crashes and brass which all accentuate the final 1/8th note. She starts singing and playing piano, while we are able to watch the pictures on the wall in the background of the entire family. Het movements of playing the piano do not match the actual syncopated piano, but actually show an ‘inner movement’[9] (Image 1); according to Eisenstein an ‘inner movement’ is the fundamental movement which is audio-visually expressed. The first arrow shows us the movement of the screen, after which the second arrow represents Loïs entering the space. The two red circles that follow, are accents on which Loïs stagnates in movement, on which the text and movement is emphasized by cadences and note durations. The mordent is portrayed by a zig-zag movement of Loïs with an emphasis on ‘-vies’ of ‘movies’. The tone jumps to the front in synchronization with the images towards the mordent. Then the drone, with a duration of 4 seconds, is depicted by Loïs with an ongoing movement from the left to the right.

After the four measures above, Peter enters the screen to sing his lyrics; this is complemented by a more prominent choreography by the means of arm movements and a sagittal view. The red circles in image 2 show the division of movements, where the first arrow represents the movement of shrugging the shoulders which illustrates the question ‘where?’; which is equal to the movements of the notes. Thereby, the piano and contrabass disappear and we notice an interchange between the trumpet and saxophone on the words sung by Peter to illustrate the more staccato images. During the word ‘fashioned’, Peter holds Loïs, while the pitch is also being kept stable. A sforzato of ascending hexatonic scale on brass is started to the dominant of the subdominant, after which the remaining family members, literally, jump into the frame to sing along, while the screen zooms in on them and the music is silenced for three seconds (second arrow). This scale contains an equal number of notes as family members. The quartet focus their body position to the middle. This looks like a pyramid figure, which is found back in the score, which, combined with the words and the zooming in from earlier on, portray the ‘centre’ on which they lean. After that, a new sforzato on brass follows on the word ‘rely’, when the family members open up by accentuating that movement; their bodies could literally be seen as a personation of the sound and letter ‘Y’.

The setting is changed from living room to a showcase setting including costume, décor and choreography. The verbal space;[10] distribution of syllables overarching the musical sentence, are represented in the movement of the legs; when multiple syllables are used, the tempo of the moving legs is doubled. All instruments play along in the chorus: trombones, piano, contrabass, crash cymbals, guitar, trumpet and saxophone. They turn their hats and canes on the word ‘positively’ of ‘a man who, positively can do’ as portrayal of the three measures (see appendix 1; measures eleven, twelve and thirteen) with a likeness in structure and continuity. When the family Griffin walks up the stairs, you’ll see dancing figures on the side who turn out to be prominent neighbor’s from the show. They all point during the word ‘us’ of ‘all the things that make us’ to family Griffin in the middle. On which Stewie answers with ‘laugh and cry’, without any further instrumental guidance. After that, the ‘camera’ rolls up the stairway, an accelerating sequence is started and the main characters, one by one, step onto the highest platform on accentuated percussion and brass during the words ‘our family’ to further illustrate the story. To finalize the song the screen takes on a top view, while zooming out of a television that functions as a dot in the I in the title screen of Family Guy.

When you read and hear the lyrics you could assume which direction my argument is going to take. The text literally starts with naming the topics on television which do not match with the utopic family life. The text Loïs sings (see appendix 2), doesn’t fit the role appointed to her in the show, which is one of the responsible mother figure. The text of Peter about ‘good old-fashioned values’ is a reference to the fifties, sixties and seventies. We can make this assumption from the context of a musical occupation of a swing-band with jazzlike characteristics in the form of cancan dancing. This form of cancan, can be a reference to the musical Can-Can of Cole Porter from 1953, which became huge hit in Amerika and was turned into a movie in 1960 with Frank Sinatra playing one of the characters. The image of Peter is, as we see in Homer’s case, painted with ‘violent’ brass, to, probably, indicate his reckless and contrasting role and behaviour unlike Loïs. The choice to let, specifically, him sing these lyrics, show a gender role more in favor of males. Then, the entire family Griffin sing ‘on which we used to rely’. When we take on a traditional stance, this could be interpreted economically for the male, as Loïs has a more emotional supporting role for the family. We can hear this more emotionally role due to the more virtuoso instrumentation. The same division of roles is to be found back in the musical introduction of the family members of The Simpsons. Subsequently, there is a referring back to the sentences of before with ‘Lucky there’s a family guy’ as a solution for the designated tv-problem, after which a reference to the animatic aspect is used:

Lucky there's a man who

Positively can do

All the things that make us...

[Fill: Stewie Griffin ]

Laugh and cry!

The aspect of cartoons characters not suffering from permanent damage, just like in the presentation of the idyllic suburb of The Simpsons, is brought to light through the word ‘positively’; or so to say, they can do whatever makes us laugh and cry. The text ‘laugh and cry’ thereby also refer to Stewie’s actual age. MacFarlane also choose to apply a literal choreography instead of a rhythmical editing in the form of a choreography. This could be a reference to the irony of the show. Which is a form of self-mockery against the use of animation. Through the ‘inner movement’ we also see that the Mickey Mousing aspect of cartoons is brought back in every aspect and layer of the show. We see a slightly mathematical emplacement in the choreography and in the background we see sprinklers that may point towards Busby Berkeley’s spectacles 42nd street and Footlight Parade both from 1933.

The references towards to musical film accord to the often used content of Herzorgs[12] musical moments or more specific; production numbers, in Family Guy. These are moments in which the images are construed upon a foundation of music, mostly, containing the length of a pop song. They are fragmented and often contain a flawed contextual unity. Because of this, the repetition in form and differences in approach and content clearly come to the front. This form is ideal to raise questions about sociocultural and political problems. Besides, the nature of a musical moment consists of patterns of repetition that are open to receive interventions of chance, just like the utopic dystopia of the provincial American family life of the anicom. In other words; the applied choreography is a form of self-mockery against cartoons, but also a manifestation of and reference to production numbers, which indicate the setting of the show in terms of form and are frequently deployed to raise socially sensitive subjects.[13]

See below the interpretation of Metz’ model that should indicate the setting of the program:

Spoken word: ‘It seems today, that all you see, is violence in movies & sex on tv. But where are those good old-fashioned values on which we used to rely. Lucky there’s a family guy’

Music: swing-band occupation, instrumental variation per family member

Visual images: homely setting, family construction, cancan dance, mathematical show line-up and fountains.

Sound: singing voices

Written word: Family Guy

—> Family Guy takes place in the family life of the fifties, sixties and seventies

The television that’s introduced in the show’s title is the finishing touch of the title song. The rotating camera of the first beat leaves the audience with a feeling of peeking through a window, and thus getting an insight of their family life; this fourth wall effect is a common detail of the sitcom. At the end, this fourth wall is broken down, by giving the family a sense of consciousness of the camera presence and zooming out of the tv to the title screen. This is, off course, a reflective reference to earlier sitcoms, but also a self-reflection; as the show often refer to films and television in the form of satire. Within this, another form of self-mockery is to be found, as the show constantly comments on itself and ridicules the channel FOX. Furthermore, the lyrics are about violence and sex on tv, while the show implements these elements all the time. Next to the ironic values, the imaginary gadget-conscious setting is brought to the front; you’ll jump out of a tv in which you just witnessed a ‘perfectly synchronized show’, just like the way in which The Simpsons draw upon the provincial family life as the ultimate human condition.

The three levels that Fiske described are all to be found in my analyses. Some more important than others. There are quite a few parameters to be found to represent the cartoon, but that wouldn’t be an overarching interpretation or ideology. And so, rhythmical choreography, Mickey Mousing, hit points and lyrics are used to emphasize the form of animation. I’ll mark animation as a code of style and structure. Besides, the ‘sprint to the television’ or ‘couch-scene’ and the Lydian scale are used in accelerated tempo of the The Simpsons and the lyrics, the television in the form of a dot in the I and the usage of a production number, characterize the imaginary gadget-consciousness. But I wouldn’t necessarily draw this aspect as a whole ideology. Both theme songs use musical variation to introduce the personalities of the characters. The Simpsons does this through thematical variation and Family Guy does this through instrumental and textual variation. Added to that are the images of Springfield in daily life, the setting of a cancan dance and the occupation of a swing band that all point towards the provincial American culture of the fifties, sixties and seventies.

The imaginary gadget-consciousness and the imaginary animation are used to put the setting of the family life of fifty or sixty years ago as an ideal picture, which shapes tools to find the ideology of the anicoms. There are a lot of defects to be found within this setting of this provincial family life. Characterizing is the representation of the relationships between family members, mostly shown as dysfunctional. And so, the neighborhood of The Simpsons is established as chaotic and the irony of Family Guy concerns the deployment of sex and violence in the show, while the, often used, element of television is emphasized constantly to bring the viewer to a state of awareness. The ideology of the show tries to, in my opinion, create an utopic dystopia. Critical statements are made about the world we live in through this utopic dystopia combined with the absurdity, irony and comedy. This critical stance fits the target audience of adults, considering that kids won´t notice these remarks at all. This ensures that the cartoon generates a new audience, indeed.

My conclusion, thus, would be that the genre anicoms not necessarily brings any specific characteristics to the front during the intro songs, but focus more on audiovisual codes so the viewer understands that the cartoon is intended to be interesting and entertaining for adults. With the goal to continue watching. The model of Fiske fits, because of this, better as a tool for my analysis than the one of Metz. These codes differ per show, but do point towards the same overarching structures. These structures are the usage of animation, the imaginary gadget-consciousness and the setting of the provincial American family life a half a century ago. These structures are, then, bound by the means of irony, comedy and absurdity, as a result of which the whole show in virtually every scene establishes an utopic dystopia. With this, socio-cultural, political and self-critical points of views are made; which manifests the genre anicoms to be entertaining for adults.

———————————————————————————————————

[1] Nichola M. Donson, “The Fall and Rise of the Anicom: the Sitcom Genre in U.S. TV Animation (1960 – 2003)” (PhD thesis, Queen Margaret University, 2004), 280-282.

[2] Ronald Rodman, “Towards an Associative Theory of Television Music,” in Tuning in: American Narrative Television Music (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), 20-21-24.

[3] Rodman, “Towards an Associative Theory of Television Music,” 26-27.

[4] Martin Kutnowski, “Trope and Irony in The Simpsons’ Overture,” Popular Music and Society 31, no. 5 (December 2008): 599-600.

[5] Kutnowski, “Trope and Irony in The Simpsons’ Overture,” 600.

[6] Kutnowski, “Trope and Irony in The Simpsons’ Overture,” 601-603.

[7] Edward J. Fink, “Writing The Simpsons: A Case Study of Comic Theory,” Journal of Film and Video 65, no. 1-2 (lente/zomer 2013): 50.

[8] Kutnowski, “Trope and Irony in The Simpsons’ Overture,” 604-608.

[9] Nicholas Cook, “Multimedia as Metaphor,” in Analysing Musical Multimedia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 57-59.

[10] Dai Griffiths, “From lyric to anti-lyric: analyzing the words in pop song,” in Analyzing Popular Music, ed. Allan F. Moore (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 43.

[12] Amy Herzog, “Introduction,” in Dreams of Difference, Songs of the Same: The Musical Moment in Film (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010), 5-7.

[13] Amy Herzog, “Introduction,” 1-8.

———————————————————————————————————

Used literatuur

Cook, Nicholas. Analysing Musical Multimedia. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Donson, Nichola M., “The Fall and Rise of the Anicom: the Sitcom Genre in U.S. TV Animation (1960 – 2003)” PhD thesis, Queen Margaret University, 2004.

Fink, Edward J.. “Writing The Simpsons: A Case Study of Comic Theory.” Journal of Film and Video 65, no. 1-2 (lente/zomer 2013): 43-55.

Griffiths, Dai. “From lyric to anti-lyric: analyzing the words in pop song.” In Analyzing Popular Music, geëdit door Allan F. Moore, 39-59. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Herzog, Amy. Dreams of Difference, Songs of the Same: The Musical Moment in Film. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

Kutnowski, Martin. “Trope and Irony in The Simpsons’ Overture.” Popular Music and Society 31, no. 5 (December 2008): 599-616.

Rodman, Ronald. Tuning in: American Narrative Television Music. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

‘NEW Family Guy Intro - (HD)’. Youtube video, 0:30. Uploaded by ‘PoyntBlankProductions’. 24 december, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WJOAvttDJ-Q.